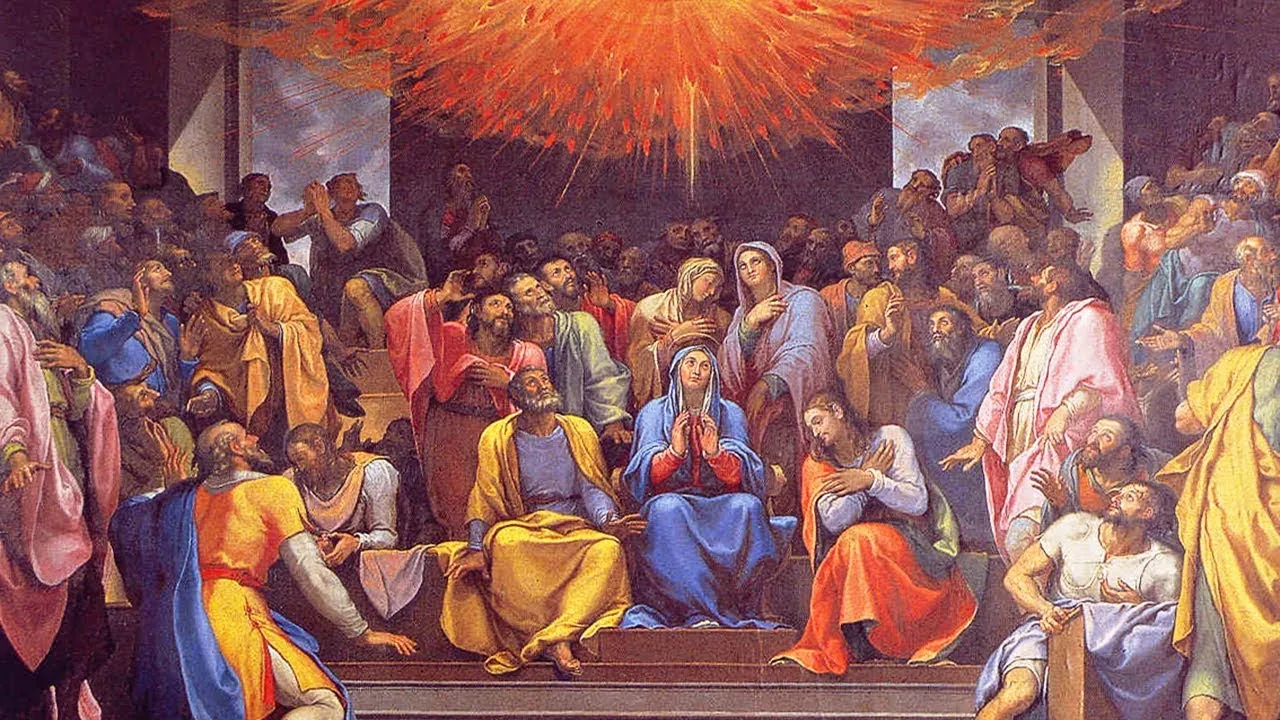

When the day of Pentecost arrived, the Jewish celebration marking the first annual wheat harvest, all the followers of Christ were gathered together in one place, just as Jesus had commanded before His ascension to Heaven. After spending time sitting, waiting, and praying, a sudden sound like a mighty rushing wind filled the entire house. Then, tongues like flames of fire appeared, divided, and rested on each of them. All were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in different languages as the Spirit enabled them.

Outside the house, thousands of devout Jews from every nation under heaven were worshiping the God of Israel, celebrating this cherished festival. The sound of the rushing wind was so loud that it drew a crowd. When the disciples left the house, praising God, the Jews were bewildered because each person was hearing them speak in their own language. The diverse crowd was amazed and asked, “Aren’t these Galileans? How do they know how to speak our native tongue? Look, they’re declaring the mighty works of God in our language!”

Everyone was filled with amazement and confusion, asking, “How is this possible? What does this mean?” However, some mocked them, saying, “They’re just drunk!”

[My Dramatization of Acts 2:1-13]

Have you ever walked into a church and heard people speaking in tongues? What was that experience like for you? Did you feel compelled to join in, or did you want to disappear into the nearest bush, like Homer Simpson?

You may have heard and even joined the joke that tongues, as they are practiced today, sound like people regretting their purchase, “I Shoulda bought a Honda! I Shoulda bought a Honda!”

While everyone would acknowledge that the gift of tongues is undeniably “biblical,” there’s significant debate about its meaning, purpose, and practice. The Bible addresses the gift of tongues in many passages, including 1 Corinthians 12:10, 12:28, 13:1, 14:4, 14:5, 14:22; Mark 16:17; Acts 2:2-13, 10:44-46, and 19:1-7; Romans 8:26-27; and Ephesians 6:18. Yet, we often struggle to reach agreement on what the gift of tongues truly is and what its for.

Underneath the gift of tongues are deeper theological disagreements:

- Are the gifts of the Spirit for today (continuationism), or did they cease after the age of the apostles (cessationism)?

- Are tongues the supernatural ability to speak unstudied foreign languages (xenolalia), as seen in Acts, or are they ecstatic utterances directed “to God, not men… uttering mysteries in the Spirit,” where “my spirit prays, but my mind is unfruitful,” as Paul describes in 1 Corinthians 14?

- Is praying in tongues synonymous with “praying in the Spirit,” and is it an uncontrollable ecstasy, or a gift exercised at will, like prophecy?

- And perhaps most piercing for some: Is speaking in tongues the definitive proof of being baptized in the Spirit?

If I had only ever read the book of Acts, I might have concluded that the gift of tongues was solely for the apostolic age, a miraculous ability to speak foreign languages (xenolalia), an uncontrollable phenomenon, and a definitive sign of Spirit baptism. However, when 1 Corinthians 12-14 is brought into the mix, my conclusions shift. I see that tongues are integral to church life (continuationism), often a form of ecstatic utterance (glossolalia), and a gift given rather than a proof of Spirit baptism, because, as Paul asks, “Do all speak with tongues?” (1 Corinthians 12:30), assuming no.

Attempting to harmonize these polar-opposite descriptions of tongues is a topic so dense that I wrote a 16-page paper about it. But rather than sharing the whole thing, let me just share my three main conclusions. I hope it brings some clarity!

1. Tongues as a Sign to Unbelievers

First, the gift of tongues serves as a sign to unbelievers, pointing to a new humanity (the church) with new tongues (Mark 16:17) indwelt by the Spirit of God. Each occurrence of tongues in the book of Acts, aligned with the Great Commission in Acts 1:8 to be witnesses “to the ends of the earth,” marks the inclusion of a new group—Jews, Samaritans, and Gentiles—into God’s family through the reception of the Holy Spirit.

In Acts 2, for instance, the miraculous sound of rushing wind gathered a crowd who were astonished to hear Galileans speaking in their own languages. This phenomenon served as a clear sign, setting the stage for Peter’s sermon. Peter refuted accusations of drunkenness, instead declaring that this event fulfilled Joel’s prophecy: “And in the last days it shall be, God declares, that I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh…” (Acts 2:17a).

Similarly, 1 Corinthians 14:22 reinforces this purpose, with Paul stating that the gift of tongues is “a sign to unbelievers.” He quotes from Isaiah 28:11-12: “In the Law it is written, ‘By people of strange tongues and by the lips of foreigners will I speak to this people, and even then they will not listen to me, says the Lord.’” As evidenced in Acts, the gift of tongues was predominantly a sign to unbelieving Israel. Because they had rejected Jesus as the Messiah, God opened the doors for people of every nation and tongue to receive the Holy Spirit through faith in Jesus Christ.

2. Tongues as a Speech to God in an unknown language

In both the book of Acts and 1 Corinthians, the gift of tongues consistently manifests as prayer or praise in a language unknown to the speaker. This can be either xenolalia (the use of foreign languages) or glossolalia (ecstatic utterances). Importantly, this communication is always directed to God, not to people, and serves as a direct response to the Spirit’s grace and activity. Far from being uncontrollable, these are utterances that overflow from the heart, primarily serving to edify the speaker. This stands in contrast to prophecy, which is directed to people, spoken through individuals by the Spirit, and delivered in a language that is understandable for the edification of the church. Interestingly, these two gifts are often found together.

Paul clarifies this distinction in 1 Corinthians 14:2-4: “For one who speaks in a tongue speaks not to men but to God; for no one understands him, but he utters mysteries in the Spirit. On the other hand, the one who prophesies speaks to people for their upbuilding, encouragement, and consolation. The one who speaks in a tongue builds up himself, but the one who prophesies builds up the church.”

We observe this dynamic modeled in Acts 2. The Galileans, filled with the Spirit, praised God and declared His mighty works in previously unknown languages that were nevertheless understandable to the hearers. While this phenomenon bewildered the crowd, it was Peter’s prophetic message, not the tongues, that convicted 3,000 Jews to repent and be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of sins and to receive the gift of the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:38).

Similarly, in response to the preaching of the Gospel and the move of the Holy Spirit, Cornelius and his entire household began to “speak in tongues and praise God” (Acts 10:44-46). Likewise, when Paul laid hands on the disciples in Ephesus, the Holy Spirit came upon them, and “they spoke in tongues and prophesied” (Acts 19:1-7). These examples from Acts clearly illustrate Paul’s teaching in 1 Corinthians 14:14 and beyond: tongues are always speech directed to God, whereas prophecy conveys speech to others, ultimately serving to build up the church.

3. Tongues as Public & Private Gifts

The gift of tongues and prophecy are distinct, yet the gift of interpretation introduces another crucial element to the puzzle (1 Corinthians 12:10). This specific gift enables someone to supernaturally understand and convey the meaning of a tongue. Critically, in public gatherings, the gift of tongues must always be exercised in an “fitting and orderly way” and be accompanied by interpretation (1 Corinthians 14:40).

This distinction is vital. Unlike the Day of Pentecost, where everyone automatically understood the tongues (glossa) spoken in their own language (dialektos), the tongues at Corinth clearly required a separate gift of interpretation for the church to comprehend them. In fact, Paul explicitly instructs the tongue-speaker in 1 Corinthians 14:13 to “pray” for this interpretation. If tongues were consistently manifest as known foreign languages (xenolalia), there would be no need for this specific spiritual gift of interpretation. People would either understand the message directly in their own language (as at Pentecost), or if no one present spoke that particular foreign language, they could simply find a human translator, or today, pull out Google Translate! The key point is not praying for a human translator, but praying for the gift of interpretation to manifest. This very need to pray for an interpretation strongly implies that the speech itself is inherently supernatural, suggesting these are ecstatic utterances that require a divine key to unlock their meaning for others.

It is in this sense that we understand tongues as a devotional prayer language directed to God—praying not with one’s mind, but with one’s spirit in a language unfamiliar to one’s understanding. Yet, in a public church gathering, if someone feels moved by the Spirit to speak their devotional prayer language aloud, it must be prayerfully interpreted for the congregation in a prophetic manner. This is because an interpreted tongue reveals the mysteries spoken in the Spirit, conveying them in understandable language prophetically for the edification of the entire church. Otherwise, if there is no one to interpret, the tongues-speaker should keep their tongues private in the church, “speaking to himself and to God” (1 Corinthians 14:28).

Final Thoughts

For much of my life, particularly during my seminary studies, my faith relied heavily on intellectual understanding. As someone who is gifted in teaching, I’ve always tried to master the Bible and even master understanding God, yet we all know it would take three eternities to fully grasp the fullness of God! Recently, a brother in Christ offered a profound encouragement: he laid hands on me and declared, “Mitch, I can see that you strive intellectually. I challenge you and bless you with the gift of tongues.”

Naturally, I began researching tongues (go figure!). Soon after, I started practicing a devotional prayer language, responding to the Lord’s gentle prompts. This practice has become one of the most relieving and enjoyable spiritual disciplines in my life. It’s taught me to quiet my mind and speak to my Heavenly Father with the simple trust of a child, much like a baby crying out to its father. Just as a father knows the unique cry of his child and exactly what that child needs, even though the baby can’t express itself in understandable language, our Heavenly Father understands the depths of our spirit’s cries. The Spirit, I’ve found, intercedes on our behalf, interpreting even our wordless groans. He knows what I need before I even ask (Matthew 6:8). Trusting that the Spirit searches my heart and guides me into God’s perfect will (Romans 8:26-27), I now express myself in prayers that transcend the limits of human language.

So, my friends, I encourage and bless you: earnestly desire the gift of tongues. Ask for it, and when the Lord prompts you, just speak out. Don’t worry about how it sounds—simply obey. Maybe it’ll be xenolalia (foreign languages) or glossolalia (ecstatic utterances); who knows? What’s important is that your spirit is praying, not your mind. This is faith in action! You never know how God might use this incredible gift in your life.

What are your thoughts or experiences with the gift of tongues? Share them in the comments below!

***A highly recommended book is Don Basham’s The Miracle of Tongues, which features over thirty documented testimonies showcasing the miracle of tongues. These are true stories illustrating God’s supernatural power at work in the lives of His children as they speak in a devotional prayer language, with listeners understanding in their own dialects.

There are four common elements present in all the testimonies:

- The individual feels compelled by the Spirit to speak in a devotional prayer language.

- The speech is directed to God in the presence of other people.

- The speaker is unaware of the actual content being spoken.

- The listener—often a skeptic or unbeliever—understands the message in their own language and praises God.

0 Comments